Sensitive communication around euthanasia

Telling a client their beloved pet needs to be put to sleep can be one of the most challenging and stressful parts of the job. It can also be an opportunity to really make a difference when we help make a tough situation just that little bit easier. Get it right and you’ll have a bonded client for life, get it wrong and you might be left ruminating on what happened or reading a complaint letter. When it comes to sharing difficult news, there are ways to make it less onerous to deliver and easier to bear. No one size fits all when it comes to a euthanasia consult. However, the good news is that research has demonstrated there are specific skills that can support us in handling challenging consultations and that practising them with simulated clients, in workshops like those organised by VDS Training, can help develop them. To that end, consider the following scenario.

Bruce is in a bad way

Earlier in the week Mr Henderson, a long-standing client of the practice, presented Bruce, a 13-year-old crossbred. You examined the dog and noted symptoms of weight loss, poor appetite and, on palpitation, a swollen abdomen resulting from what you suspect is a large intestinal tumour. Subsequently, blood tests revealed organ failure and today you must break the news to Mr Henderson that the best option for Bruce is euthanasia but, when you do, Mr Henderson is distraught and cannot understand why nothing can be done to save Bruce. “I thought you’d open him up, whip out the lump and I’d be taking Bruce home with me today. My wife will be heartbroken,” Mr Henderson explains. VDS Training employs similar scenarios in many of the courses and programmes we organise. These often incorporate experiential workshops where actors and participants play the role of the client and/or the veterinary practitioner. These role-playing exercises offer course participants an opportunity to practice skills and understand things from both perspectives. Key themes regularly emerge from these sessions which help explain why Mr Henderson, our client in the above scenario, reacted in the way he did. Reflecting on these themes also gives us a sense of how to handle this and similarly demanding situations.

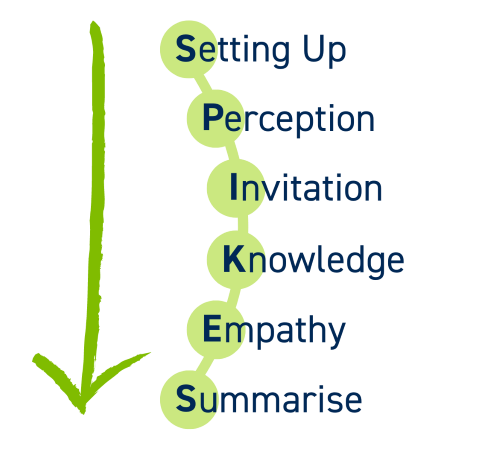

Remember that often more than one ‘warning shot’ needs to be delivered and this will have more impact and give the client time to prepare themselves if followed by a pause. Giving clients the chance, early on in a conversation, to explain how poorly they think a patient is can help start the acceptance process. It also means that it is possible to adapt the discussion to the client’s perception of the situation. Information is more easily understood if it is delivered in ‘chunks’ and does not contain any jargon. This is an interesting one, because the majority of vets know to allow time for their clients to process information. But the reality is that we often underestimate how much ‘wait time’ we need to allow. This goes further than listening – it means that instead of thinking about what we are going to say next, we should give all our attention to the client, even if there’s an awkward silence. It’s helpful to acknowledge comments like this, remember to ‘say what you see’ – for example ‘I can see this is a really upsetting situation and I that it’s going to be difficult to tell your wife’. Avoid feeling you have to solve every problem: just acknowledging what you hear from your client is often enough. In contrast, another interesting point we often hear is: Vets often worry about showing emotion, but clients generally read this as empathy. Sharing rather than repressing your feelings can also help with your own wellbeing. These reflections are the tip of the iceberg, and there is so much more we can do to improve our understanding of our clients and how we sensitively manage emotionally charged interactions with them. Finally, try to think about the before and after. Preparation is key: how can you set yourself and the environment up for success? Prepare yourself: pressing pause, popping the to do list to one side for a moment and being fully present for the client can really help. Always check in with yourself afterwards – you may feel able to rush on to the next consult, but give yourself permission to pause and take a break if you need, a couple of minutes outside might be all it takes. If you are feeling the strain, find someone to talk to, see if another team member can pick up a couple of tasks for you. Debriefing emotional situations like this can be really helpful to buffer against compassion fatigue and might be something you want to think about doing in your practice. Although all communication involving breaking bad news cannot follow an exact protocol, the SPIKES model can help you stay on track. SPIKES stands for Setting up, Perception, Invitation, Knowledge, Emotions with Empathy, and Strategy or Summary. This approach was designed by Walter Baile and colleagues at the University of Texas, and is designed to help healthcare professionals while breaking bad news:'I didn't have any warning that it was bad news'

'Nobody asked me how I thought Bruce was doing'

'I didn't hear what the vet was saying - there was too much information'

'I didn't have enough time to take the information in'

'They weren't interested in my wife's feelings'

'I felt this vet cared because they were upset too'

Setting Up

Setting the stage for optimal communication by preparing what to say prior to the conversation is essential to successful communication. Setting up also includes giving some attention to the physical space and the manner in which the news will be shared.

Perception

The client’s perception of the news to be shared will determine how the news is conveyed. The veterinary practitioner must have a good assessment of what the client already knows about the illness and the prognosis and their views on the pet’s current quality of life.

Invitation

Ask your client if they are ready for you to share some difficult news. This can ask as a warning shot, help your client prepare for what is coming and allow them to ask for more time and space if they need.

Knowledge

Think about what the important bits of information to share are. Giving some warning that the news is not good can help prepare clients to hear difficult things. Don’t overload your client with details: they can always ask for more information if needed. Take it slowly, it can take time to digest news you might not want to hear.

Empathy

It’s important to empathise throughout these conversations, an appropriate and kind response to any emotion shown when the client hears bad news is especially important. Say what you see: ‘I can see this is not the news you were hoping for’ ‘I can see how difficult this is for you’.

Summarise

Be sure to recap and clarify with the client any decisions made and actions to be taken after the conversation. Following a euthanasia for example, this would include plans for care of the pet’s body and any follow up support offered. It may also be helpful to recap the reasons for deciding to proceed with euthanasia and validating the decision made: ‘he was an old boy and was looking tired, the meds didn’t seem to be helping anymore. I’m sure it was the right time for him’.

Help is at hand

As well as providing veterinary communication training, VDS Training is here to offer support, development and coaching for you, your veterinary team, and the wider veterinary profession, so you can focus on the animals in your care. Explore our range of courses, workshops, and online programmes here.

About VDS Training

VDS Training are passionate about developing all members of the veterinary team, to help you overcome the personal and professional challenges you face on a daily basis, and to build practical skills and techniques to make a real difference to you and your life.